The First Line of the Second Stanza of Lowekks Poem for Thenunion Dead Reads Once My Nose

- How many poems are in Emily Dickinson's oeuvre?

- What do the terms "fascicle" and "fix" hateful?

- The few poems published in Dickinson's lifetime, and poems in the early on editions, take titles, simply the later on editions do not. Did Dickinson give her poems titles?

- Did Emily Dickinson date her poems?

- Is it easy to distinguish what is a poem, and what is a letter, in Dickinson'due south manuscripts?

- What are the words, the marks, the initials, and the numbers that precede the poems on some of the manuscripts? Were they made by Dickinson?

- What are the marks within Dickinson's poems, and the words at the lesser, in the margins, and in a higher place or below words, in some poems?

- Why do the transcriptions of the poems look different from the poems as Dickinson wrote them on her page?

- Why practice some lines appear in two different poems in the Johnson and Franklin editions?

- Why does more than one manuscript appear when I blazon in a outset line?

- I want to look at the original. Tin can I practise that, and if so how?

- Would I be immune to reproduce an image on my blog/in a paper/in a thesis/a book?

1. How many poems are in Emily Dickinson'southward oeuvre?

R. W. Franklin'due south 1998 variorum—the well-nigh recent and comprehensive edition of Dickinson's poems to appointment—contains one,789 distinct poems; of these ane,789, 1,685 can be traced to manuscripts equanimous in Dickinson's mitt, while the remaining 104 are reproduced from transcripts made by Susan Dickinson, Frances Norcross, Martha Dickinson Bianchi, Mabel Loomis Todd, and Millicent Todd Bingham, and from published sources including the Youth'southward Companion and the Independent. The number "1,789," however, is not stable. First of all, many of Dickinson's poems exist in more than 1 draft or version. When nosotros include the number of manuscript versions in our count, the number rises from 1,789 poems to 2,357 poem drafts or versions. Second, editors have not always agreed about what constitutes a "poem." Questions such every bit "Is a letter a poem?" or "When does a variant version of a verse form become a new poem?" trouble hard and fast tallies of Dickinson's poems. Third, nosotros cannot know that all the poems Dickinson wrote survived, or have been institute.

Back to elevationtwo. What do the terms "fascicle" and "prepare" mean?

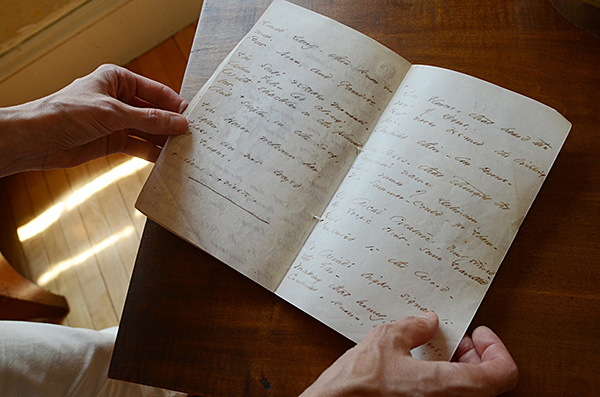

Photo credit: A reproduction of a fascicle. Courtesy Emily Dickinson Museum, Amherst, MA.

"Fascicle" is the name that Emily Dickinson's early editor, Mabel Loomis Todd, gave to the homemade manuscript books into which Dickinson copied hundreds of poems, probably beginning in the late 1850s and continuing through the late 1860s. Dickinson synthetic the fascicles past writing poems onto sheets of standard stationery already folded in two to create two leaves (four pages). She so stacked several such sheets on top of each other, stabbed two holes in the left margin through the stack, and threaded string through the holes and tied the sheets together. Occasionally she varied this bones design by binding half-sheets (cutting along the fold) into the stack of folded sheets. "Set" is a term first used past editor R.W. Franklin to describe groups of unbound sheets of similar paper and size that were never bound by the poet. There are xl fascicles, and 15 sets.

Dickinson herself did not number or label the fascicles. They were taken apart past the starting time editors of Dickinson's poesy, and and then accept had to be reconstructed past diverse scholars. Within this site, we use the order established by R.W. Franklin, The Poems of Emily Dickinson (Cambridge: Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press, 1998). Non all Dickinson scholars agree with his reconstruction.

For additional reading about fascicles, see Mary Loeffelholz, "What is a fascicle?" in Harvard Library Message New Series 10:i (Spring 1999) 23-42

Dorsum to top3. The few poems published in Dickinson's lifetime, and poems in the early editions, have titles, but the later editions practice not. Did Dickinson give her poems titles?

Titles were added by Dickinson's early editors because it was customary for published poems to accept titles. If y'all look at the images of the manuscripts, you lot will encounter that Dickinson did not title her poems. Subsequently editors such as Thomas Johnson and R.W. Franklin use the first line of the poem as a "title." Johnson and Franklin also assigned numbers to the poems, based on their attempts to establish a chronology.

Only nine of Dickinson's known poems had titles assigned to them, according to R.W. Franklin, Poems (1998), Appendix 6:

| Title | First line | |

|---|---|---|

| Snow flakes | I counted till they danced and then | (Fascicle two) |

| Pino Bough | A plume from the Whippowil | (Fascicle 12) |

| Purple | A color of a Queen is this | (Fascicle 39) |

| "Nay" Susan! | The guest is gold and crimson | (sent to Susan Dickinson) |

| Whistling under my window | Heart not so heavy as mine | (sent to Kate Anthon; original lost) |

| Baby | Teach him when he makes the names | (sent to Mary Bowles) |

| The Bluish bird | Before you lot thought of spring | (on a surviving draft; and on lost originals sent to Louise and Frances Norcross, and to Helen Hunt Jackson) |

| The Bumble Bee's Organized religion | His piffling hearse like figure | (sent to Gilbert Dickinson) |

| Diagnosis of the Bible, by a Boy | The Bible is an untold book | (on a typhoon) |

Dickinson as well referred to a very small number of other poems using brief phrases or nouns without quotation marks and ofttimes without definite articles. In an 1883 letter to Thomas Niles, an editor at Roberts Brothers in Boston, for case, she enclosed four poems, referring to one of them ("No brigadier throughout the yr") as "the Bird" and another ("A route of evanescence") every bit "A Bustling Bird."

Back to superlative4. Did Emily Dickinson date her poems?

With the exception of poems included in dated letters (e.g. "Every bit by the dead we love to sit"), Dickinson did non appointment the manuscript copies of her poems. In efforts to establish a chronology for Dickinson'southward manuscripts scholars have analyzed her handwriting, dated the paper she used, and drawn on postmarks and other means of dating letters continued to poems.

In her early letters and poems, Dickinson used a adequately conventional cursive hand (where the letters are joined together), but over the course of the 1860s this changed gradually only substantially, then that by the mid-1870s her ligations (combinations of joined messages) had almost entirely disappeared.

These methods of dating are conjectural and imprecise. Nor can they tell us with certainty when Dickinson actually equanimous a verse form, since we cannot know whether she wrote out earlier copies that were destroyed or lost. At best, they let us to assign a crude date to Dickinson's surviving manuscripts.

Dorsum to topv. Is it easy to distinguish what is a poem, and what is a letter, in Dickinson's manuscripts?

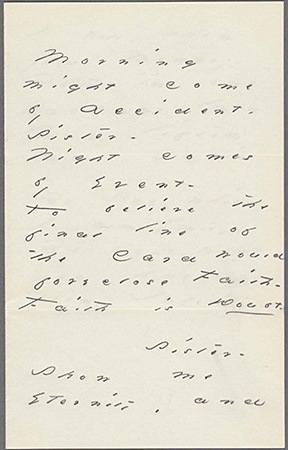

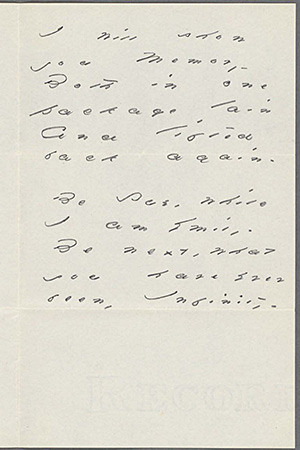

In some instances, editors of her piece of work disagree about where a letter ends and a poem begins. For example, in this manuscript:

did she see the get-go part every bit a "letter" and the second as a "verse form" when she moved from (this transcription is line-by-line):

Morning time

might come

past Blow,

Sister -

Night comes

by Event -

To believe the

final line of

the Bill of fare would

preclude Faith -

Faith is Dubiousness -

to:

Sister -

Show me

Eternity, and

I will show

you Retentivity -

Both in i

package lain

And lifted

back again -

Exist Sue, while

I am Emily -

Exist adjacent, what

you lot take ever

been, Infinity —

Hart and Smith in Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson's Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson, draw all of these lines as a "letter-poem" to Susan. R.W. Franklin considers the second "Sister-" a signature for the first grouping of lines, rather than equally function of the verse form.

Such editorial decisions influence how one counts "poems" on the one hand and "letters" on the other.

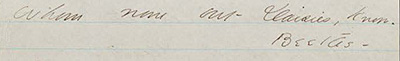

Back to tophalf-dozen. What are the words, the marks, the initials, and the numbers that precede the poems on some of the manuscripts? Were they made past Dickinson?

No. Marks unremarkably institute at the tiptop of the manuscript folio, rather than inside the poems, were made by Dickinson's early editors.

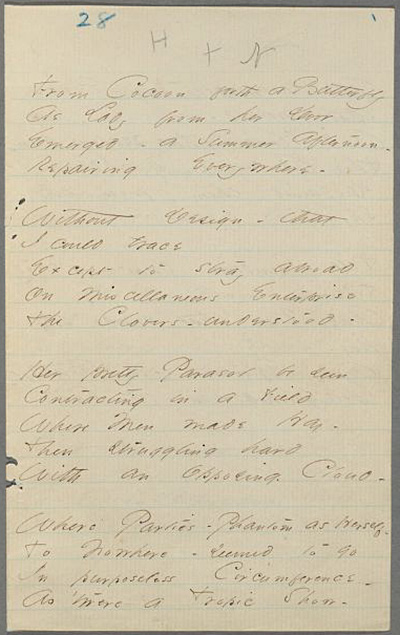

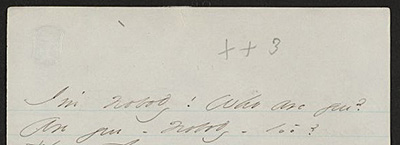

The commencement page of Fascicle 29 shows a number of such marks at the elevation of the page.

R.W. Franklin in his "Introduction" to The Manuscript Books (1981) interprets these editorial marks as follows. Lavinia Dickinson, the poet's sister, turned the manuscripts over to her sister-in-law, Susan Dickinson, to prepare them for publication shortly afterward Emily Dickinson's death. Susan Dickinson'south messages D, F, 50., N, P, S, and W occur at the head of poems in several fascicles. The letter H is probably as well hers. The pregnant of these letters is not clear, although they peradventure point certain themes: Northward for a poem about nature, D for decease, L for beloved or life, for example, possibly suggesting a way of organizing the poems into topic clusters for publication. The numbers in blueish pencil are generally ascribed to Mabel Todd or her copyists; and the lightly written "no" to Martha Dickinson Bianchi, noting that the poem had non been published.

Susan Dickinson'due south numbers 1, 2, and 3 likewise appear on the manuscripts (non on this instance, but meet "I'm nobody! who are you?").

Franklin also attributes the X, Xx, 30 markings to Susan Dickinson.

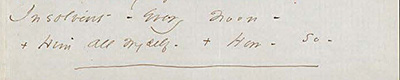

Back to meridian7. What are the marks within Dickinson'southward poems, and the words at the lesser, in the margins, and above or beneath words, in some poems?

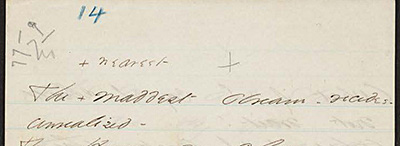

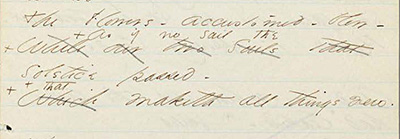

The picayune "+" signs, or crosses, which Dickinson placed near a word on the line indicate a variant to that word. A variant may appear above the word, equally in "The maddest dream recedes unrealized":

Here, in that location is a + before the word "maddest," while to a higher place it, and keyed to information technology by some other +, is the alternative "nearest." In many poems Dickinson did not cull among the variants, allowing them to stand as non-exclusive alternatives. In the re-create of "The nearest dream recedes unrealized" that Dickinson sent to T.Due west. Higginson, she adopted all three variants in this poem ("nearest" for "maddest"; "Lifts" for "Spreads"; and "bewildered" for "defrauded," each pair linked by + signs).

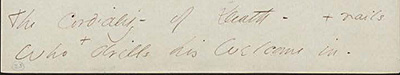

Variants may also appear to the side of a line, as in the penultimate line of "That afterward horror that 'twas us":

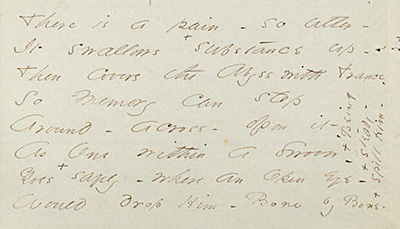

Or at right angles to the verse form, as in "There is a pain so utter," where three variants to words are written sideways on the right margin of the sheet:

Or underneath a word, as in the last line of "Of bronze and blaze," where a variant to a word is listed underneath that word (here without the + sign):

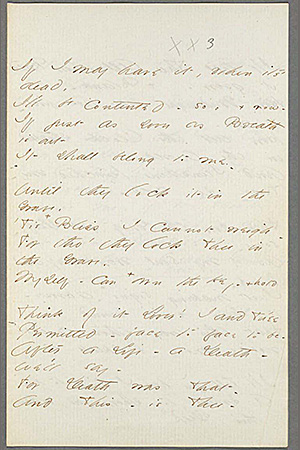

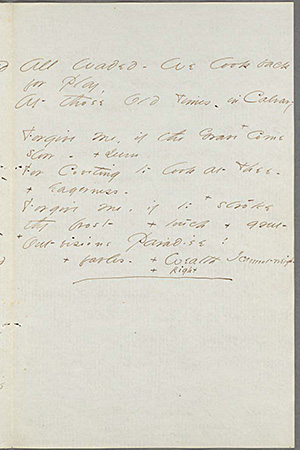

In "I gave myself to him," variants are noted at the lesser of the fascicle sheet:

At times, Dickinson seems to be fitting variants into the available blank space on the fascicle sheet, without regard for compatible placement. For example, in "If I may have it when information technology's dead," the variant may be to the side of the word; to the side of the line; below the line; or at the terminate of the poem: "Wealth I cannot weigh," a near-complete poetic line, is a variant for "Tis Bliss I cannot weigh", while "Right," (copied below "Wealth" ) is an alternative to both "Bliss" and "Wealth." Every bit the last instance illustrates, Dickinson may provide more than i variant for a given discussion.

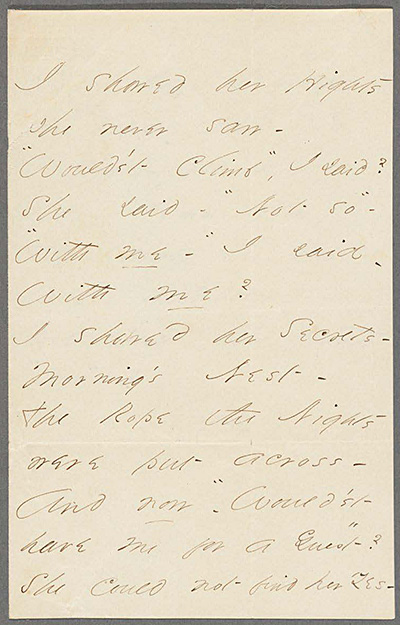

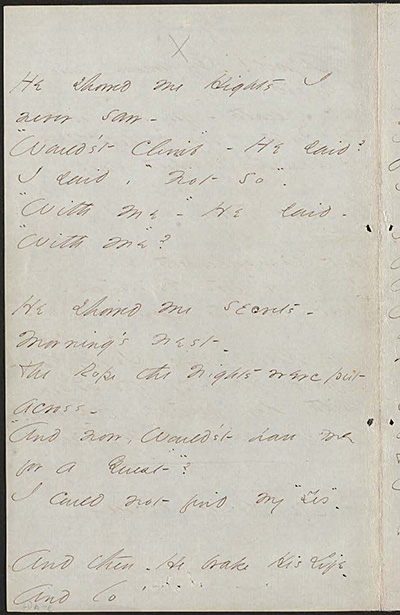

Whole poems may exist variants of each other. Thus "I showed her hights she never saw," which Dickinson sent to Susan Dickinson, has a variant in Fascicle sixteen, "He showed me hights I never saw," in which the gender is changed, as well as the positions of lover and speaker ("I could not notice my 'Yes'—" replacing "She could non find her Yes—" in the re-create sent to Susan).

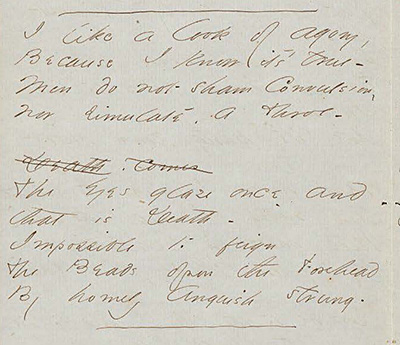

Very occasionally, Dickinson drew a line through a word, indicating a decision to cancel one word and substitute some other, as, for instance, in "I like a look of desperation," in which in the beginning line of the second stanza "Death, comes" is decisively crossed out and replaced by "The Eyes glaze one time—and that is Death—,":

and in "There came a mean solar day at summertime's full," where a determination against discussion choices is marked by lines through those words.

These examples are drawn from Sharon Cameron, Choosing Not Choosing: Dickinson's Fascicles (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

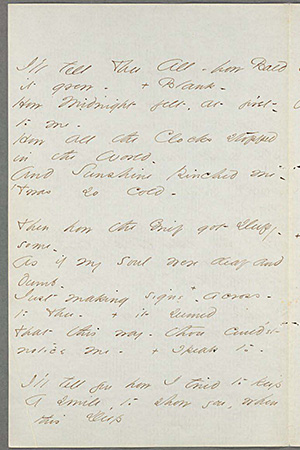

Dorsum to top8. Why do the transcriptions of the poems look different from the poems equally Dickinson wrote them on her page?

Historically, near editors of Dickinson's poems have regarded them as cast in metrical forms, hence their transcriptions follow conventional stanzaic and metrical cues rather than the visual arrangement of the words on her manuscript pages. More recent editors sometimes lineate their transcripts following Dickinson's visual line on her manuscript folio.

Back to meridian9. Why do some lines appear in 2 dissimilar poems in the Johnson and Franklin editions?

Thomas H. Johnson and R. Westward. Franklin practise not e'er agree on how to translate the manuscript page. For example, while Johnson ascribed the following lines of Houghton MS Am 1118.3 (157) to the penultimate stanza of "I tie my hat I pucker my shawl" (Johnson 443/Franklin 522), Franklin ascribed the lines to "A pit but heaven over it" (Franklin 508/Johnson 1712), a poem for which, with the exception of the five lines in question, the manuscript is lost.

These are the lines: "'Twould starting time them--/We—could tremble--/But since we got a Bomb--/And held it in our Bust--/Nay—Hold it—information technology is at-home—."

Franklin argued that Dickinson used a unmarried sheet, Houghton MS Am 1118.3 (152), on which to copy the conclusions to ii separate poems.

Back to peak10. Why does more than ane manuscript appear when I type in a outset line?

Dickinson oftentimes copied a poem more than once, and so at that place are several extant autograph manuscripts for some poems.

Back to pinnacle11. I desire to look at the original. Can I do that, and if and so how?

This site includes images of manuscripts held at many unlike libraries and athenaeum, and each will have its own policy about access. You should contact the library/archive and ask; there is contact data listed under Partners and Credits.

Back to summit12. Would I be allowed to reproduce an epitome on my weblog/in a paper/in a thesis/a book?

The content of this site is governed by a Creative Eatables Attribution-Non-Commercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) (available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode).

You are allowed to use an prototype found in EDA on your blog, or in a classroom projection or assignment Just you besides need to credit the library/archive that holds the original manuscript (this is listed nether the image) and the EDA. For use in a book or thesis, you do need permission; please contact the establishment listed as holding the original manuscript. Contact data can be found under Partners and Credits. For more than information, see Copyright and Terms of Use.

Back to topSource: https://www.edickinson.org/faq

0 Response to "The First Line of the Second Stanza of Lowekks Poem for Thenunion Dead Reads Once My Nose"

Post a Comment